50 European Museums in 50 weeks

Science Gallery Dublin | Humans Need Not Apply

February 18, 2017

The Science Gallery is an unusual museum, in that its goal is to use science and art to provoke discussion on issues. This is somewhat different from art museums where objects are displayed for their intrinsic value and from science museums who use exhibits to teach visitors. This exhibit both educates and raises questions about progress in the field AI and robotics, the replacement of human workers by machines, and the implications for society.

The Science Gallery is an unusual museum, in that its goal is to use science and art to provoke discussion on issues. This is somewhat different from art museums where objects are displayed for their intrinsic value and from science museums who use exhibits to teach visitors. This exhibit both educates and raises questions about progress in the field AI and robotics, the replacement of human workers by machines, and the implications for society.

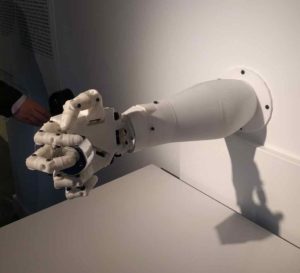

I particularly liked the first object in the exhibit: HUMANS NEED NOT TO COUNT, a robot hand, made from 3D printed parts, which clicked a “clicker” to count people entering the gallery. Like a number of the items on display, it was not working when I visited, but this did not bother me too much — it showed that the work here were prototypes, not products. I liked how the piece showed how people could be replaced in the context of guards at the exhibit itself, and also the whimsey of the piece – once a sensor had identified that someone had come in, it would be much simpler (but less expressive) to just have a computer keep the count.

In a similar vein, a device with buttons labeled “coffee”, “check” and “service” was put on every table of the gallery’s café. This highlighted one of the themes of the show, that “creativity”, “service” and “caring” were the types of work that that are least able to be automated, though progress in AI is may endanger these jobs as well.

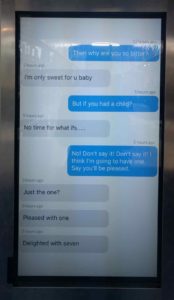

Another piece that was more thought-provoking than functional was Lady Chatterly’s Tinderbot. This piece featured conversations on Tinder with an AI “chatbot” which used dialog from D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. While the AI did not seem to be very convincing at conversation, the strangeness of its answers did not seem entirely out of place in the strange world of anonymous tinder chats, so participants were fooled into engaging with it. For me, this demonstrated in a humorous way how some human interactions can be replaced by machines without much “intelligence”.

The Next Rembrandt was again a piece where human’s reaction to the piece is more important than the technology on display. This piece was created by J. Walter Thompson Amsterdam, an advertising agency, is a “3d printed painting” created by an AI using data from scans of Rembrandt paintings to select the subject, composition, lighting, and even brush strokes for a new painting which is intended to feel like it was created by Rembrandt. The Science Gallery says it is unclear what was the computer’s contribution vs. that of human artisans and designers, but they point out the “1.8 billion media impressions, according to J. Walter Thompson Amsterdam”, showing how interested we are interested in the idea of computers creating “old master” artwork. The Science Gallery was unable to obtain the painting for the exhibit so, in an ironic twist, they hired a human to paint a copy of the computer generated “original”, and displayed that along with a video about the original project.

Minimum Wage Machine uses technology to demonstrate how little human work is valued in our society. This machine delivered a one cent coin when a visitor turned a crank for 3.892 seconds, turning the €9.25 an hour minimum wage in Ireland into an experience. For the typical gallery visitor, who most likely makes far more that that, the drudgery to get so little is made physical by this machine. The fact that the gallery could give away the coins in this exhibit, and the fact that many visitors simply left the dispensed coins in the machine also demonstrated how little money the minimum wage represents. While this piece does not directly address computer automation, it demonstrates both how tedious and low paying many jobs are that are at risk of automation.

5000times is another piece that demonstrates the tedium of human manual labor, in this case the manual labor involved in creating mobile phones and laptops. One case shows the tape that is hand cut and applied during the assembly of a MacBook. A pile of tape is exhibited, showing the amount applied by one worker in one day, along with a pile of 5000 glass phone screens representing how many screens a human at an iPhone plant would be expected to place manually (a job currently too precise for robots).

Other works attempted to show how machines could take over some ritualistic repetitive tasks, while showing the absurdity of automating them. Stony 1.0 is a robot designed to clean and leave flowers and stones on a tombstone, in accordance with Jewish custom. This brings to mind the question of what tasks can but should not be automated? If the purpose of this ritual is to help remember the dead or to do some simple work to pay homage to their memory, or to show a sign that a loving person has visited, then the ritual becomes meaningless once it is automated.

Another piece, The Mindfulness Machine, is a robot that makes geometric “doodles” and then colors them in with pen. The explanatory panel tells us that as robots approach human sophistication, they will feel anxiety and stress, and they could use coloring as a way to “chill out”. The machine picks designs and colors based on its mood which is in turn are based on a complex algorithm with inputs including the weather, ambient noise, how many people are watching, and various biorhythms. The idea that humans and thinking machines would be so similar as to be helped by the same “meaningless” creative repetitive tasks, seems amusing and rather absurd, but it does challenge the viewer to think about the what makes us human, what is the meaning of creativity and “mindfulness”.

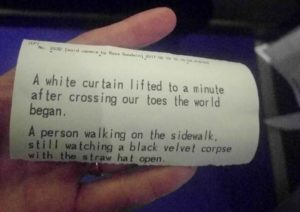

word.camera is a piece where a camera generates poems based on what it sees, which are printed out on slips of paper. Visitors are invited to pose for poems, which they are given to take home. The project is built out of an antique camera body. While the “poems” seem to be only tangentially related to the portraits (the camera is easily distracted by background elements) reading them can evoke emotion in a similar way to modern poetry. This piece got me thinking about creativity and the creative role of the person reading a poem separate from the expressiveness of the words, and how the ambiguity of modern art and poetry can nurture this participation by the reader/viewer.

These are just a few of the engaging exhibits in this show which is successful in raising important questions of our day.

© 2026 50Museums.eu | Theme by Eleven Themes

Leave a Comment