50 European Museums in 50 weeks

Het Scheepvaartmuseum | The Atlases

April 25, 2017

The other day we saw an intriguing poster which I just had to translate — it turned out to be for the National Maritime Museum (Het Scheepvaartmuseum) in Amsterdam for a show about cartography in the Dutch golden age. Intrigued, we put it on the top of our list of museums to visit, and when we saw it, we were not disappointed.

The other day we saw an intriguing poster which I just had to translate — it turned out to be for the National Maritime Museum (Het Scheepvaartmuseum) in Amsterdam for a show about cartography in the Dutch golden age. Intrigued, we put it on the top of our list of museums to visit, and when we saw it, we were not disappointed.

I am traveling this year in Europe with my wife, Donna David, who is a university professor on sabbatical studying maps. We have been lucky that our travels have corresponded with some great exhibits about maps at the British Library, the National Library of Scotland, and now here.

The Dutch “golden age” is the 17th century, when the Dutch were the world leaders in trade, military, science and art. Map making put art and science at the service of trade and military might, so it is not surprising that the Dutch were the best in the world.

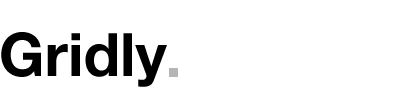

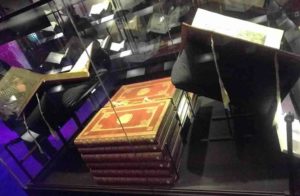

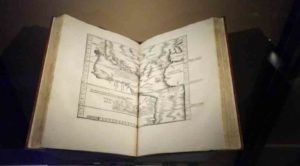

The exhibit started with a series of atlases based on the works of Ptolemy, a second century cartographer, astronomer and scientist in Alexandria. In the 1400’s, at the start of the Renaissance, these books were “rediscovered” and brought to Rome, and map makers used Ptolemy’s work to create their own atlases. Ptolemy’s maps themselves had been lost, but not his tables of places known in the ancient world with associated coordinates. This information was far more complete than anything else known in the 15th century, making it invaluable for the Dutch traders and the map makers that supplied them. One atlas in the show, printed in Rome by Bernardus Venetus de Vitalibus, was based on Ptolemy but also included a plate with a map by Dutch explorer and cartographer Johannes Ruysch. It’s one of the very first maps of the New World. It was not uncommon to update atlases with the latest information.

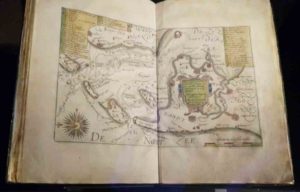

The exhibit included some Dutch charts for sailors, including individual maps as well as others bound into books on navigation. These are based on the experiences of generations of sailors, who noted the distances and direction they sailed. The charts are intended for sailors, and have lots of details of coastal towns and geography, but almost no detail of interior areas. They even included some routes and bearings for common routes. This was in contrast to the atlases (a term coined by Willam Jansz. Blaeu), which were much more ornate and were intended more for study or as objects to show off one’s wealth, knowledge and good taste.

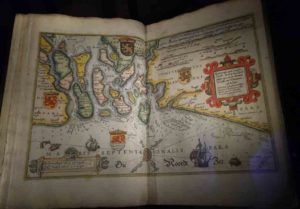

The rest of the exhibit concentrates on the atlases of Dutch master cartographers and publishers Mercator, Claesz and Willem and Joan Blaeu. Mercator is best known for his innovative Mercator projection. Using this projection to render the spherical earth as a rectangular map, all latitudes and longitudes become straight perpendicular lines. While maps designed like this do not accurately represent distances or sizes (arctic regions such as Greenland are represented quite large), they do accurately represent directions, which makes them valuable for navigation. The exhibit included a nice display which projected light through a globe onto a section of a cylinder, physicalizing Mercator’s calculations. Mercator also designed a special italic typeface for use on his maps and globes, which he documented in a manual on display here.

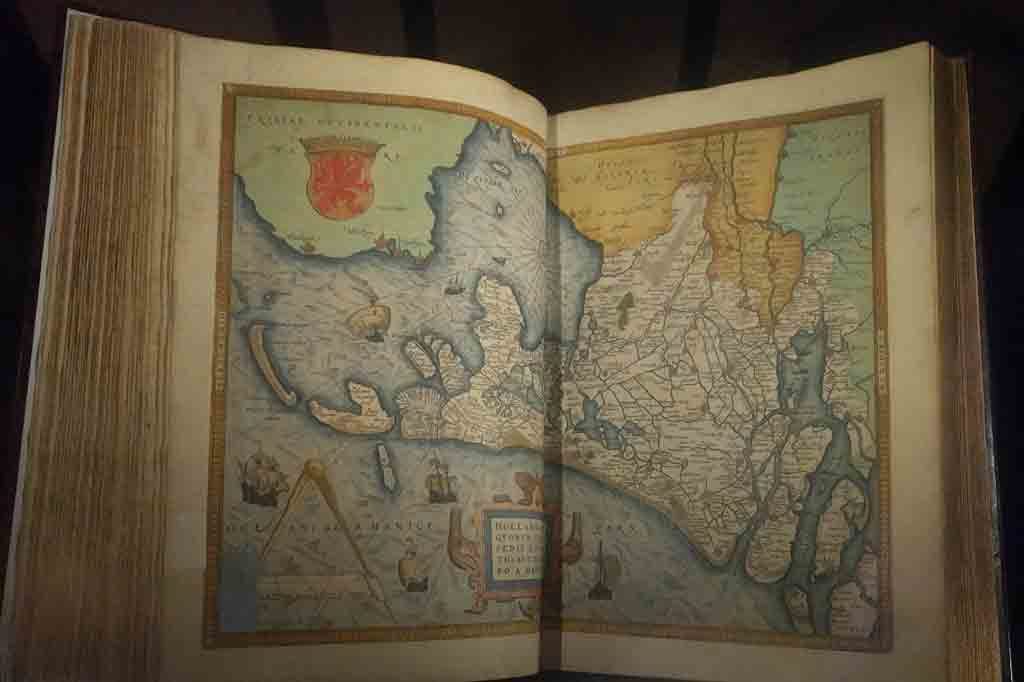

Pile of the volumes of Atlas Mayor, published by Joan Blaeu in 1664, “the pinnacle of Dutch atlas production” according to museum notes. It was the largest and most expensive book in the 17th century

The maps of these masters are beautiful and fun to study. Some of the volumes on display are open to maps of the world, others to maps of Northern Europe and of areas including Amsterdam, which are of special interest to visitors to this museum.

The exhibit featured two large interactive displays, allowing visitors to see all the pages of several atlases featured in the show. These helped get a sense of these publications as a whole, rather than just the one spread on display. There were also back-lit blow-ups of illustrative details from maps and an full wall animation of maps to engage the visitors and to emphasize the beauty of the maps.

The show left me with a sense of awe, and an appreciation of the Dutch role in the history of maps.

© 2026 50Museums.eu | Theme by Eleven Themes

Leave a Comment